Crohn’s disease is estimated to have a prevalence of 157 per 100,000 in the United Kingdom.[i] The condition is more commonly seen in individuals from northern climates, and people of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry (often geographically from Eastern Europe and Russia).[ii]

The pathophysiology of Crohn’s disease is complex, and it is thought a combination of the following factors can lead to the development of Crohn’s disease:

1. Genetic susceptibility

2. Dysregulated immune response

3. Environmental exposures and triggers

4. Disruption in the gut microbiome

Genetic Susceptibility and Dysregulation of Immune Responses

Many gene mutations are associated with the development of Crohn’s disease, a major one being NOD2. The NOD2 gene is involved in regulating immune responses in the gut for example, by suppressing Th17 immune responses. NOD2 also protects the host by detecting components of bacterial cell walls e.g. muranyl dipeptide (MDP). Detection of this promotes killing of intracellular bacteria. Mutations in NOD2 can lead to exaggerated immune responses, inflammation and insufficient clearing of invasive bacteria.

Environmental Exposures

People living in developed regions may benefit from a more sanitary environment and thus less exposure to microbes, which would otherwise have helped develop the gut microbiome and immunity (hygiene hypothesis). Thus, living in areas of higher sanitation which is actually a risk factor for Crohn's disease.[iii] Environmental factors such as smoking and poor diet can affect the gut microbiome.

Disruption in the Gut Microbiome

The diversity of the gut microbiome has been shown to be reduced in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Precise reasons as to why this is the case is still being researched though some theories exist, such as genetic factors leading to reduced variability in the gut microbiome. The gut microbiome is crucial for immune regulation in the bowel e.g. it forms an epithelial barrier and regulates immune responses.

Adherent invasive E.coli bacteria have been isolated in many individuals suffering from Crohn’s disease. These bacteria induce inflammation by releasing the inflammatory cytokine TNF-alpha and are resistant to xenophagy (process by which intracellular bacteria are degraded using phagosomes and lysosomes).[iv] This further adds to the inflammation in the bowel.

Gastrointestinal Manifestations

Extra-Intestinal Manifestations

Pyoderma Gangrenosum

Systemic Manifesations

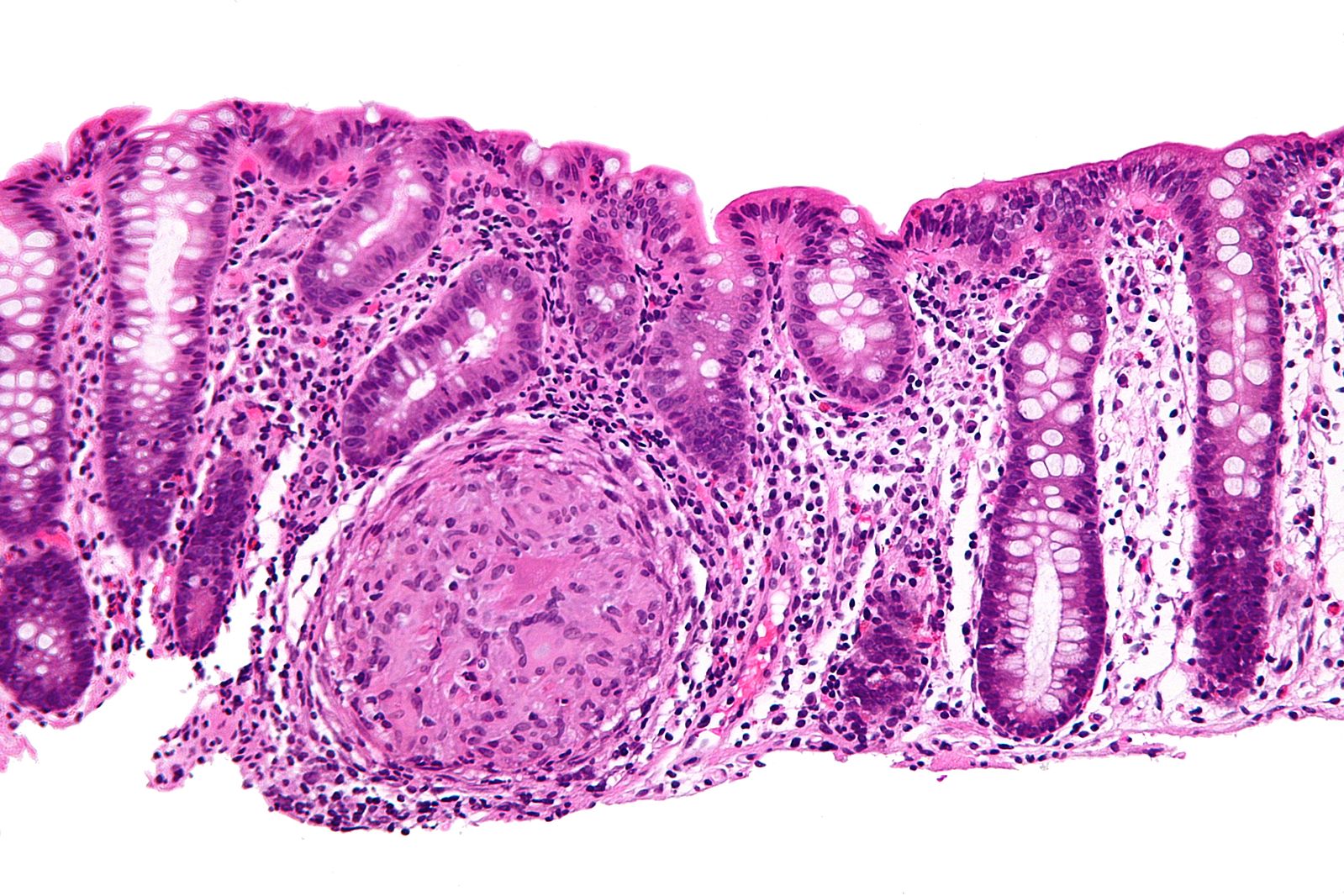

Histology of Crohn's Disease

Bloods

Stool

Colonoscopy

Colonoscopy with biopsy is extremely important for diagnosis as the bowel can directly be visualised and a pathologist can look for characteristic features of Crohn’s disease as described above. The British Society of Gastroenterologists recommends that biopsies be taken from the ileum, rectum and a minimum of four colonic sites.[viii]

Perianal disease can develop due to inflammation of the anus. Perianal fistulas are investigated with examination under anaesthesia which involves a normal examination (inspection, palpation) but under general anaesthesia.[ix]. [x]

Management focuses on two main things; either you're trying to induce remission, or you're trying to maintain remission. We'll go through each scenario in turn.

Inducing Remission – In the case of one exacerbation in a 12-month period

Inducing Remission – In the case of 2 or more exacerbations in a 12-month period

Maintaining Remission

Remission is typically maintained with azathioprine, although mercaptopurine can be used as well. If these are contraindicated, methotrexate can be offered. Steroids are not used to maintain remission.

Biologics

Biologic treatments are monoclonal antibodies. TNF-alpha has been shown to play a role in the pathogenesis of Crohn’s, so this is a common target for biologics e.g. infliximab and adalimumab. Biologics can be used in severe disease which has not responded to steroid/immunosuppressive treatment. It is important to monitor side effects and assess the patient to look for improvement. These drugs are started by specialists.

Surgery

Surgery should be avoided where possible, particularly since disease could recur elsewhere in the GIT. Indications include failure to respond to drug treatment, fistulae or intestinal obstruction. Several types exist:

[i] GP Online. Crohn’s disease – Clinical review. [internet]. 2017. [cited 18th August 2019]. Available from: https://www.gponline.com/crohns-disease-clinical-review/gi-inflammatory-bowel-disease/crohns-disease/article/1213250#1

[ii] Feuerstein JD and Cheifetz AS. Crohn Disease: Epidemiology, Diagnosis and Management. [internet]. 2017. [cited 18th August 2019]. Available from: https://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org/article/S0025-6196(17)30313-0/fulltext#sec2

[iii] Dutta AK and Chacko A. Influence of environmental factors on the onset and course of inflammatory bowel disease. [internet]. 2016. [cited 20th August 2019]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4716022/

[iv] Boyapati R, Satsangi J and Ho G. Pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease. [internet]. 2015. [cited 20th August 2019]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4447044/

[v] Choi D, Jin Lee S, Ah Cho Y, Lim HK, Hoon Kim S, Jae Lee W et al. Bowel wall thickening in patients with Crohn's disease: CT patterns and correlation with inflammatory activity. [internet]. 2003. [cited 20th August 2019]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12565208

[vi] O’Dowd G, Bell S and Wright S. Wheater’s Pathology: A text, Atlas and Review of Histopathology. 6e. Elsevier. 2020.

[vii] Medscape. What is the role of chronic inflammation in the etiology of hypoalbuminemia. [internet]. 2018. [cited 20th August 2019]. Available from: https://www.medscape.com/answers/166724-41459/what-is-the-role-of-chronic-inflammation-in-the-etiology-of-hypoalbuminemia

[viii] Feakins RM. Inflammatory bowel disease biopsies: updated British Society of Gastroenterology reporting guidelines. [internet]. 2013. [cited 20th August 2019]. Available from: file:///Users/HR/Downloads/BSG%20guidelines%20on%20inflammatory%20bowel%20disease%20biopsies.pdf

[ix] Medscape. Evaluation of perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. [internet]. 2005. [cited 20th August 2019]. Available from: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/503224_4

[x] Kumar and Clark’s

[xi] Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin 2009;47:9-12.

[xii] NICE. Crohn’s disease: management. [internet]. 2019. [cited 20th August 2019]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng129/chapter/Recommendations#providing-information-and-support

[xiii] Crohn’s & Colitis UK. Surgery for Crohn’s disease. [internet]. 2019. [cited 20th August 2019]. Available from: http://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/files.crohnsandcolitis.org.uk/Publications/surgery-for-crohns-disease.pdf