Dyspepsia is a group of symptoms colloquially known as indigestion. It can be caused by a range of conditions such as peptic ulcer disease, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), gastritis or infection with helicobacter pylori (H.pylori). Functional dyspepsia (also known as non-ulcer dyspepsia) is also a possible cause whereby patients have symptoms of dyspepsia but no ulcers.

Symptoms of dyspepsia include:

A peptic ulcer is a break in the epithelial lining of the stomach (gastric ulcer) or duodenum (duodenal ulcer). The majority of peptic ulcers are duodenal.

There are two major causes of peptic ulcer disease - overuse of non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) and secondly, H.pylori infections.

Other causes include Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, a rare condition gastrin producing tumours lead to excess stomach acid production which ultimately leads to ulceration.

Frequent use of NSAIDs can lead to a peptic ulcer due to inhibition of the cyclo-oxygenase enzyme 1 (COX-1). Phospholipids in the body are converted into arachidonic acid which can subsequently be converted into prostaglandins via two enzymes - COX-1 and COX-2.

NSAIDs non-selectively block both COX-1 and COX-2 leading to inhibition of gastro-protective prostaglandins as well as inflammatory prostaglandins.

H.pylori infections are another common cause. H.pylori bacteria possess a urease enzyme which converts local urea into ammonium and bicarbonate ions which allows them to neutralise stomach acid and thus evade the toxic gastric environment. Infection with this bacterium is thought to cause local gastric inflammation which can lead to gastritis, peptic ulcer disease and stomach cancer.

Gastric Ulcer

Red flag symptoms that may suggest an upper gastrointestinal tract bleed include haematemesis/coffee-ground vomit and melaena.

NICE recommend that people presenting with dyspepsia be offered a H.pylori test. However, if the patient is simultaneously being tested for H.pylori and being treated with a PPI, it is important to be off of PPIs for at least 2 weeks prior to the test.

Diagnosis of H.Pylori Infections

| Invasive | Non-Invasive |

| Biopsy urease test: A biopsy of the stomach is added to a urea-containing medium which is marked with a coloured indicator such as phenol red. If H.pylori is present is will convert the urea to ammonium which causes a colour change from red to yellow. | Serology: A blood test is used to identify IgG antibodies against H.pylori |

| Histology: A biopsy specimen can be used to detect H.pylori on histology. | 13C-urea breath test: Involves swallowing 13C marked urea. If H.pylori is present, the urea will be converted to ammonia and carbon dioxide. Isotope labelled 13CO2 is then measured in the breath. |

| Culture: Biopsies can be cultured, and antibiotic sensitivities can be tested | Stool antigen test: Stool specimen is used to look for evidence of H.pylori infection. |

Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD)

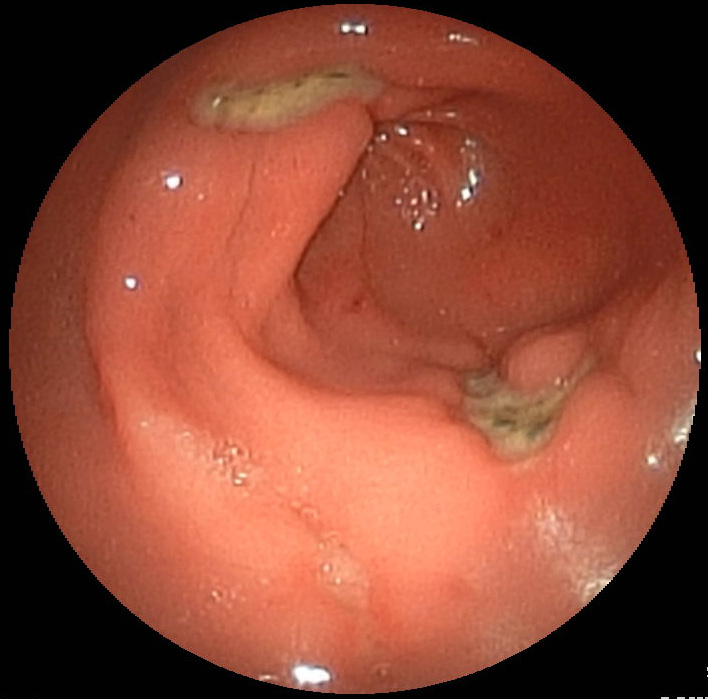

This involves passing an endoscope through the mouth into the stomach in order to directly view the stomach. It can also be used to gain a view of the oesophagus and the duodenum. It is usually performed with the patient fully conscious or sedated, depending on the preferences of the patient.

It is vital to do an immediate (same-day) OGD with any signs of significant GI bleeding. Additionally, anyone presenting with red flag symptoms such as dysphagia, unexpected weight loss or anaemia (with associated gastrointestinal symptoms) should be referred for endoscopy.

Example of Gastric Ulcer in the Antrum of the Stomach

People with dyspepsia should be offered a full-dose PPI for 4 weeks (alongside a H.pylori test as described above for which the treatment will be different if the patient is positive). A H2RA can be offered if there is insufficient response to a PPI.

H.Pylori

Patients with peptic ulcer disease who test positive for H pylori should be offered eradication therapy which involves one of the following regimens:

Re-Testing

Drug-Induced Ulcers

H.Pylori Negative and Patient is not Taking NSAIDs

Peptic ulcers may bleed which may lead to signs of an upper GI bleed which includes haematemesis, coffee-ground vomiting and melaena. Likewise, ulcers can also perforate leading to extreme pain and peritonitis.

Gastric outlet obstruction can also occur as a result of a healed ulcer which has scarred or due to oedema surrounding an ulcer. This tends to present with projectile vomiting in very large quantities and may contain whole parts of a meal. Stenting or dilating the pylorus can be performed to manage this.

Kumar and Clark’s

Oxford Handbook

NICE Guideline: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG184/chapter/1-Recommendations#interventions-for-peptic-ulcer-disease-2